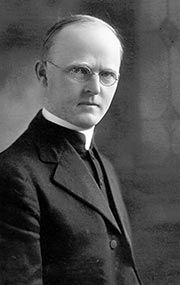

Edwin Vincent O'Hara

By Lucinda A. Nolan

Catholic

Edwin Vincent O’Hara (1881-1956), Roman Catholic priest, prelate, educator, social activist and scholar is considered the father of the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine in the United States. He was influential in the areas of social justice, Catholic rural life reform, and the defense of parochial schools. He was the catalyst for the revisions of the Baltimore Catechism and the Douay-Rheims Bible. In the field of religious education Bishop O’Hara remains unsurpassed in his dedication to providing teacher training and publishing catechetical resources. His work to promote correspondence courses, vacation religious schools, CCD, and Catholic adult discussion clubs provided innovative ways for children and adults to grow in their understanding of the Catholic faith.

Biography

Early Life

Edwin O’Hara was the last of eight children born to Owen and Margaret O’Hara. He was born on September 6, 1881 on a farm that covered three hundred and twenty acres in Amherst, Minnesota. Edwin O’Hara was baptized in St. Patrick’s Church in Lanesboro, Minnesota on October 2, 1881, by Father James Coyne.

Edwin’s father, Owen O’Hara, was a farmer who experimented in the diversification of crops and the development of new breeds of cattle (Dolan 1992, 4). Edwin’s mother, Margaret Nugent O’Hara, sewed the family’s clothes and saw to the education of the children, in addition to her daily farm chores. The O’Hara’s valued education and built a schoolhouse on outskirts of their property. To their credit, Owen and Margaret O’Hara sought to hire the best available teachers for the children of their township.

Margaret O’Hara was an experienced catechist and student of theology, having taught catechism classes as a young woman in Indiana with Father Sorin, CSC, missionary and founder of Notre Dame University (Shaw 1957, 2). This background helped her to soundly instruct her children in the Catholic faith and prepare them for reception of the sacraments. Mass attendance for young Edwin was irregular since not all of the O’Hara children could fit in the family carriage to make the nine-mile trip to the nearest Catholic parish in Lanesboro, Minnesota (Shaw, 6). Edwin prepared for confirmation by taking classes with adult parish catechists. Fr. Coyne who pastored the Lanesboro parish for forty-one years was the first priest young Edwin knew. He remained a mentor to Edwin for many years.

Home study sessions in the O’Hara home took place around the kitchen table where Owen, an avid reader of classical literature, set an example for the children by learning along with them as Margaret taught the lessons. The children received what Margaret and Owen believed to be the best kind of education—a balanced life of farm chores and studying. All eight of the O’Hara children went to college and a few went on to post-ĚŇ»¨ĘÓƵ schools. “Faith, family, farming, learning (were) all guiding values throughout the seventy-five years of Edwin Vincent O’Hara’s life . . .” (Dolan 1992, 1). “Never did he regret the diligence, obedience, and self-discipline, the reverence for family and nature, nurtured on the land” (Dolan 1992, 4).

Early Education

Young Edwin began his formal schooling with his older sister Anna as his teacher in the little schoolhouse his family built on the outskirts of their farm. It was a public school and the majority of the students happened to be Norwegian Lutherans. These circumstances were formative to the later development of Edwin’s ecumenical point of view (Shaw, 7). Edwin learned the Lutheran Catechism in the Norwegian language while attending vacation bible schools conducted by the Lutherans. Many years later, Father O’Hara would adapt the concept of summer religious education to rural Catholic areas.

Following primary school (1895), Edwin boarded with family friends in town in order to attend Lanesboro High School. It was here that his vocational calling as a priest began to gradually awaken. His parish priest in Lanesboro, Father James Coyne, taught Edwin to read Greek, but did little to persuade or dissuade him about ordination (Shaw, 8). Edwin steadily grew in his conviction that he was called to the priesthood.

In January of 1898, at the age of thirteen, Edwin O’Hara entered The College of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. Founded by Archbishop John Ireland to be a seminary, the college later became open to all. Edwin enrolled in classical studies and took classes with the excellent faculty hired by the Archbishop. While at St. Thomas’ he helped edit the student literary newspaper, The Sybil, (Dolan 1992, 10). Edwin was an excellent student.

By the time of his graduation in June of 1900, Edwin was certain he wanted to return to school as a candidate for the priesthood at the newly established St. Paul’s Seminary, whose founder and superior was Archbishop Ireland.

In the fall of 1900, O’Hara entered St. Paul’s Seminary to study for the priesthood (Shaw, 13). Archbishop John Ireland, who was already known to the young seminarian from his days at St. Thomas, became a “second powerful priestly influence on Edwin (Dolan 1992, 11).

St. Paul’s Seminary

Edwin’s years in the seminary gave shape to the kind of priest and minister he would become, though his upbringing remained heavily influential as well. O’Hara would later recall of Ireland, “When I entered the seminary, the archbishop was at his prime; his personality radiated through the halls. . . . (He) left upon us an indelible impression of intellectual power, strength of conviction and apostolic purpose” (Dolan 1992, 11). From Ireland, O’Hara learned to confront issues head-on, to harmonize Catholic truths and American ideals, to approach economic and political issues progressively, and to view science and scholarship as compatible with religion (Dolan 1992, 11—13).

While attending seminary, O’Hara again had the opportunity to study with a world-class faculty. He took philosophy with Fr. William Turner; psychology with Fr. John Seliskar and English with Fr. William H. Sheran (Shaw 1957, 17). In addition, he studied moral theology with Fr. John A. Ryan and listened to the lectures of Bishop John Lancaster Spalding who strongly influenced the young priest’s ideas on education. Both Ryan and Spalding affirmed O’Hara’s strong sense of social justice that had been instilled by his father.

While a student at St. Paul’s, Edwin O’Hara wrote two articles, both of which were published in the Catholic University Bulletin in 1903. The articles, “Religion as a credible doctrine” and “Skepticism as a basis of religion” both dealt with the compatibility of religion and science. Amazingly, while still involved in the rigorous program for seminarians at St. Paul’s, O’Hara translated a full text by a German Catholic scientist, Dr. Eberhard Dennert, with help from a fellow seminarian and friend, John Peschges (Dolan 1992, 15). The translated edition, entitled At the deathbed of Darwinism, was published in 1904. The book was an “excellent refutation of the false philosophy that had arisen from the great biologist’s work (Shaw 1957, 18).

Before O’Hara could finish his theological studies, he was called to an early ordination by the archdiocese of Portland (then known as Oregon City). On June 10, 1905, Father Edwin Vincent O’Hara was ordained by Archbishop Ireland. Providentially, one of his earliest sermons was on Acerbo Nimis, an encyclical by Pope Pius X on catechetical instruction in the Faith for the young (Shaw 1957, 25).

Father Edwin Vincent O’Hara left home for Oregon at the end of July 1905, to begin a long and important ministry in the Church. By 1930, O’Hara was named Bishop of Great Falls, Montana, and in 1954 he was appointed by Pope Pius XII to become Archbishop ad personam. Cardinal Stritch gave the sermon on the occasion of O’Hara’s elevation:

We could say many things in congratulating him this morning but we think that we say it all when we say to him that under the inspiration of Pius X he has been and is the great catechist in the Church in the United States. (Shaw, 254)

Later Years

In October of 1955, Archbishop O’Hara celebrated his Golden Jubilee as a priest and his Silver Jubilee as a bishop. At the Jubilee Mass, the Archbishop of Portland Oregon, Edward D. Howard said of O’Hara:

I wish only to show how well he has sensed the needs of our day. I wish to bring out how fearlessly he has chosen new methods, how he has analyzed our problems, prayed and sought for their solution and then proceeded to act. . . . Archbishop O’Hara was well aware of the teaching office of the priesthood, but he knew the layman could be the Church’s champion once he learned to speak. (Shaw, 259)

On September 11, 1956 Archbishop Edwin O’Hara of Kansas City, Missouri, suffered a heart attack and died while in Milan, Italy, for a conference. His service to the Church and to Catholic Christian education lasted for over five decades.

Works Cited

Dolan, Timothy M. (1992). Some seed fell on good ground: The life of Edwin V. O’Hara. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press.

Shaw, J. G. (1957). Edwin Vincent O’Hara: American prelate. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Cudahy.

Contributions to Christian Education

The influential work of Archbishop Edwin V. O’Hara touched every part of church life, nationally and internationally. O’Hara did not see his ministerial efforts as compartmentalized, but as connected and interwoven within an overall mission of handing on the faith. If there was one theme that tied together his multiform ministries it would be his dedication to following the directives put forth by Pope Pius X in the encyclical, Acerbo Nimis (1905). Archbishop Timothy Michael Dolan, biographer of O’Hara, writes that O’Hara referenced the encyclical in the celebration of his first Mass:

[O’Hara] referred to the recent encyclical . . . which dealt with catechetics, and pledged his own priesthood to evangelization and education in the faith. (Dolan, 1992, 17)

The encyclical that so shaped the ministry of Archbishop O’Hara addressed the catechism and particularly the need for instruction in the faith for Catholics of all ages. Pius X saw the importance of religious instruction of those children who did not attend Catholic schools and therefore lacked formal catechism classes. He called for the revival and establishment of the CCD (Confraternity of Christian Doctrine) in every parish (Dolan 1992, 127). Edwin Vincent O’Hara remained dedicated to the cause of effective religious education throughout his life.

The scope of Archbishop O’Hara’s work over the next five decades is vast, reaching into every corner of Church life. The following sections focus on Archbishop O’Hara’s major contributions to Catholic religious education.

Getting Started

As a young priest Father O’Hara was assigned to the cathedral parish in Portland, Oregon. There he showed expertise in fund raising, organizing parish clubs, ecumenical outreach, Catholic apologetics, and social justice issues such as unemployment, just wages, and temperance. O’Hara confronted the anti-Catholicism of many Oregonians of the time and labored for the rights of Catholics to have their own parochial schools.

Another biographer, J. G. Shaw, wrote,

Every priest in principle is an educator. From the first year of his priesthood, Edwin Vincent O’Hara was one in hardworking reality as teacher, professor, supervisor, administrator and articulate promoter of a Christian philosophy of education. (Shaw, 35)

Young O’Hara assumed responsibility for diocesan educational concerns.

In 1907 he began a Summer Institute for Teachers and organized The Catholic Education Association of Oregon (Shaw, 36). In 1910, following an illness brought on by exhaustion, Father O’Hara made his first trip to Europe where he had an audience with Pius X, the Pope whose encyclical, Acerbo Nimis (1905) had so inspired him.

Research for his book, The pioneer Catholic history of Oregon (1911), led O’Hara to better understand Dr. John McLoughlin, a Catholic layperson, as the true “father of Oregon” and to make the education of laypersons central to his own ministry.

Fr. Edwin O’Hara was appointed Diocesan Superintendent of Schools in 1912.

In 1917, O’Hara was given an honorary doctoral degree by the University of Notre Dame for his work on behalf of the Church in Oregon. O’Hara spent the following year as a chaplain in France, ministering to both soldiers and townspeople. Upon his return, the young priest requested a transfer to a rural parish. In 1919, he was named pastor of St. Mary’s in Eugene, Oregon, where he would begin his long campaign to end the Oregon School Controversy. O’Hara was instrumental in getting the case argued before the United States Supreme Court (1925) and in gaining the rights of Catholic families to make choices for their children’s education (Dolan 1992, 41—46). His rural apostolate in Eugene, Oregon was demanding, but the young O’Hara used the opportunity to extend his ministry in religious education toward new endeavors.

A Rural Apostolate

The primacy of the family among social institutions is a Catholic first principle. The ideal home is the source of population and the nursery of faith and morals. Sanctity and indissolubility are its foundation and domestic unity the keystone of the arch which supports our Christian civilization. The impelling reason for the concern of the Catholic Church with rural problems is to be found in the special adaptability of the farm home to the production of strong, wholesome, Christian family life. (O’Hara 1927, 33)

Edwin Vincent O’Hara was well suited to the rural setting of St. Mary’s in Eugene, Oregon. His upbringing in Minnesota had prepared him for much of what he found there. The parish was in ruins, a result of the failing health of its previous pastor. O’Hara built a small church and school. One month after his appointment to St. Mary’s, O’Hara presented his address, “The Rural Problem and Its Bearing on Catholic Education,” to the National Catholic Education Association. Less than a year later, he was appointed as Director of the Rural Life Bureau, and by July of 1921, he had published A Program of Catholic Rural Action. O’Hara founded the National Catholic Rural Life Conference in 1923 and, as its executive secretary, “traveled, lectured, wrote and organized the national crusade” (Dolan 1992, 74). The results of his survey and research led him to propose actions that would lead to the solution of the many problems of rural life which included isolation, lack of religious leadership and resources, decreasing population, and financial difficulties.

The proposals were seven in number, the seventh being: “Strong rural religious centers employing means of religious instruction adapted to rural conditions must be developed” (Dolan 1992, 73). O’Hara’s parish was a laboratory where he put his rural program into practice.

O’Hara’s preoccupation with education led him to become a frequent visitor to the University of Oregon campus, where he ministered to the spiritual needs of the Catholic college students. Fr. O’Hara re-organized the Newman Club to meet both the religious and social needs of the students and the organization thrived. His attention then turned to those children in outer rural areas who were not being served by Catholic parishes or schools. “In devising schemes to reach these forgotten country children, the Eugene pastor initiated programs that influenced the nation” (Dolan 1992, 54). He believed that “The future will be with the Church that ministers to the rural population.”

Father O’Hara had three solutions to the problem of inadequate instruction in the faith for these children. Firstly, Sunday school classes were formed and conducted by the Sisters of the Holy Name. Lay catechists were trained, often by O’Hara himself, to augment the Sisters’ numbers. Regardless, there were still many children who lived too far away to benefit from these parish classes.

Correspondence Courses and Religious Vacation Schools

It was in the 1920s that the church was brought to an awareness of the needs of the rural areas through the efforts of Archbishop Edwin O’Hara, who became a leading spokesman for the rural apostolate His interest eventually settled on the problem of rural pastors and ineffective catechesis through Sunday schools. He came up with two alternatives to ineffective Sunday schools, the Religious Correspondence courses and the Vacation Bible School (VBS). (Spellacy 1986, 579)

Though others had experimented with the idea, O’Hara organized correspondence courses, with illustrated texts overseen by Victor Day of the Catholic Rural Life Bureau. Each lesson consisted of an illustration, a story, formal instruction and a series of questions or an exercise. The courses centered on topics such as the creed, commandments, sacraments, lives of saints, and the history of the church (Spellacy, 580).

These courses will consist of 15 or 16 illustrated lessons, to be sent out in weekly installments during the winter season when it is difficult for country children to come to Sunday school and when country families find themselves with much time on their hands which can profitably be used for religious study. (O’Hara 1922b, 17)

The children completed each lesson under supervision of a parent, usually the mother. The written exercises were returned by mail to the parish where they were graded and returned with the new lesson for the week. Diplomas were awarded to those who completed all the correspondence courses. “The religious correspondence lesson is studied in the farm home by the whole family group under the supervision of the mother. Thus is strengthened the practice of family religious education” (O’Hara 1927, 67).

By 1923, correspondence courses were in use in twenty-seven states and in many parts of Canada (Collins 1975, 1983, 178).

The second innovative idea was one that O’Hara had experienced as a boy in Minnesota. Also organized under the Catholic Rural Life Bureau, religious vacations schools allowed rural children to attend intensive classes in faith during the summer weeks. “The religious vacation school is not in any sense a substitute for a parish school. But to a parish without a parish school it is like a spring in a desert land where there has been no way and no water” (O’Hara 1927, 61).

Lasting for about four weeks in the summer, these schools included as much content as the year-long parish religious education programs. Children attended for half a day, so that they might help with chores at home in the afternoon. “The program includes: daily Mass, teaching of prayers, Bible stories, the lives of Saints, catechism, sacred singing, recreation and health” (O’Hara 1929a, 2).

Religious vacation schools spread rapidly in the United States and were met with widespread enthusiasm. They rapidly became O’Hara’s passion and he helped to generate professionalism and uniformity among the schools in the U.S. and Canada. “By 1928 there were over three hundred religious vacation schools in operation. . . .” (Dolan 1992, 76). By 1930, there were more than one thousand such schools. O’Hara wrote,

It is of utmost importance to have trained teachers—teachers who have training in pedagogical methods and experience in dealing with children. Where possible, religious teachers should be secured . . . but lay teachers of experience and training can conduct the vacation schools with satisfaction, and there are many devoted Catholic lay teachers who will gladly give their services if their expenses are cared for. (O’Hara 1927, 62)

In 1928, the Rural Life Bureau (RLB) became a part of the National Catholic Rural Life Conference (NCRLC). As it newly named national director, O’Hara moved to Washington, D.C. and shortly thereafter published Catholic Evidence Work in the United States. In this survey, O’Hara cites the urgent need for a national movement to enhance the religious education of Catholics who through no fault of their own were “religiously illiterate” (Collins 1975, 1983, 180).

Dolan describes O’Hara’s efforts to organize religious vacation schools on the national level:

No detail in planning, location, calendar, texts, or curriculum escaped his supervision. . . . His desire to professionalize the summer catechism classes was advanced when, beginning in 1931, the NLB issued a Manual of Religious Vacation Schools, a compact, neatly arranged handbook containing suggestions for conduct of the vacation school and an outline of study for teachers. The Rural Life Bureau and subsequently the National Center of the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine published the manuals annually throughout the thirties. (Dolan 1992, 76)

Installed as Bishop of Great Falls, Montana in November of 1930, O’Hara asked the priests of his new diocese to establish the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine in each of their parishes as soon as possible. This was not a new notion but one of O’Hara’s dreams since he first read Acerbo Nimis (1905). He was now in a position to implement his experiences from the NCRLC throughout his diocese and throughout the nation.

Confraternity of Christian Doctrine

The idea of promoting the Confraternity of Catholic Doctrine on the national level was not new. In the United States, as early as 1902, CCD chapters were springing up in New York and in Los Angeles, with scattered chapters in many other states. It took the organizational skills and dedicated leadership of Edwin O’Hara to “expand formal religious education for Catholic children and youth attending public schools, as well as for Catholic adults and people of goodwill everywhere, in a year-round program sponsored by the Confraternity” (Collins 1975, 1983 180). At O’Hara’s invitation, Father Leroy Callahan, diocesan director of CCD in Los Angeles, was invited to speak to the 1930 meeting of the NCRLC. “Here for the first time, the sessions devoted to religious education were formally listed as Confraternity of Christian Doctrine sessions” (Shaw, 121). The Rural Life Bureau and the Rural Life Conference subsequently led to the development of a national CCD program. Shaw’s biography states,

Thus the first activities of the Rural Life Bureau, its vacation schools and correspondence courses which had brought parents to working with their children at religious instruction in the home, drew a straight line between the Bureau and the Confraternity. It would be quite proper to say that one grew out of the other in continuation of Father O’Hara’s constant preoccupation with bringing the truths of religion to those who needed them most. (Shaw, 121)

Back at home, in the rural diocese of Great Falls, Montana, Bishop O’Hara set out with his usual energy to implement his ideas for religious education. “O’Hara’s dream was to make the diocese a laboratory for testing and displaying two great movements within the Church in the 1930s: the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine and Catholic Action” (Dolan1992, 114). On the very day of his consecration he informed diocesan priests of his plan to establish the Confraternity in every parish of the diocese. This was followed by a pastoral letter and directives for implementation.

The pastoral ordered training courses for lay teachers since, it must be remembered, “the Confraternity is a lay organization both in origin and constitution.” The bishop also drew up plans for an extensive adult education program through study clubs. (Collins, 1975, 1983, 182)

Within a year, every parish in the diocese of Great Falls had a Confraternity and by 1933, every parish had a chairman for their adult discussion club.

On the national level, the Confraternity continued to grow in size and scope and by 1934 it split from the Rural Life Conference to become its own entity. It provided religious instruction for public school children, stressed lay involvement and training and gave methodological and substantive content to the classes. Adult and parent education was part of the Confraternity’s purpose, making it harmonious with the goals of Catholic Action for the lay apostolate of the Church in the United States. The Confraternity also allowed for the dissemination of Catholic literature to Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

In the scheme of things the Confraternity represented a program in total religious education. Instruction was not an end in itself, but a means to foster Catholic identity and inculcate Christian values. . . . A well-organized CCD unit was a beehive of activity that ran year-round. It had vacation schools for young children, sacramental preparation for First Penance and First Communion, social programs for young people, study clubs for adults, and an outreach effort for the unchurched. (Marthaler 1990, 224)

In 1934, the American bishops named an episcopal committee to oversee the CCD. Shortly thereafter, the idea of a national center was approved. It was to be located at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception on the campus of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. (Collins 1975, 1983, 183). O’Hara was appointed Chairman of the Episcopal Committee of the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine. Archbishop McNicholas of Cincinnati and Archbishop Murray of St. Paul were named members and Dom Augustine Walsh, OSB was appointed as the first director of the National Center. Archbishop Cicognani, Apostolic Delegate to the United States from the Vatican, was a strong supporter of O’Hara and the CCD.

On May 10, 1935, The National Center for CCD was opened. The purpose of the center was to oversee and coordinate organizational publications and teaching materials for dioceses requesting assistance. It became a clearinghouse for catechetical information and provided field representatives for parishes wishing to establish the CCD. “In its thirty year history the Center produced a steady flow of catechetical materials that took into consideration the developmental stages of the child and adolescent, all the while continuing to stress the importance of catechist training” (Marthaler 1990, 228)

Both the opening of the National Center and the timely publishing of the decree, Provido Sane Consilio (Better Care and Promotion of Catechetical Instruction) by the Congregation of the Council in Rome gave credence to the Confraternity and impetus to its growth in this country.

National and regional Catechetical Congresses (1935-1956) were held in various parts of the country and were heavily attended by lay and religious alike. The overarching aim was to find ways to more effectively teach the faith. Sessions were led by experts and classroom demonstrations of teaching techniques were offered. Modern pedagogical methods were taught, new audio-visual aids were presented and published materials were displayed and sold. O’Hara attended these congresses and gave major addresses at each one. These addresses were published in the Proceedings of the conventions.

Revisions

Between the years of 1936 and 1954, O’Hara oversaw major revisions of the Baltimore Catechism and translations of the Douay-Rheims Bible and the Ritual (Collectio Rituum).

This work was done through the auspices of the National Center. Bishop O’Hara lent his organizational skills and zeal to these projects. He carefully chose the best theologians and scripture scholars for the tedious tasks involved in these projects and tirelessly sought input from other bishops as each draft was circulated.

This importance of these revisions and translations cannot be overestimated. In each case, O’Hara’s driving purpose was to better catechetical efforts in handing on the faith. The Catechism had been in dire need of revision for some time. While O’Hara did not believe the catechism should be the sole text for religious instruction (scripture, liturgy, church history, music should be included) he did believe that a systematic reordering and revision of the long-used Baltimore catechism would greatly enhance catechetical programs (Dolan 1992, 156). St. Anthony Guild published the Catechism of Christian Doctrine on July 18, 1941. Other revisions followed but this text would remain a primary source for children’s CCD for the next twenty-five years (Dolan 1992, 162).

O’Hara also saw the translation of the Douay-Rheims Bible as a “Catechetical enterprise”(Dolan 1992, 163). The outdated language made it difficult for the teachers to use and students to understand. Again, beginning in 1936, O’Hara led the tedious and drawn out process that eventually led to the formation of the Catholic Biblical Association and the publication of the New American Bible. The New Testament was published in 1941, but a complete new translation was begun in 1944 to incorporate the directive of Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Divino Afflante Spiritu. O’Hara didn’t live long enough to see the final publication of the full text in 1970. This translation put the Bible in its proper and central place in catechetics and brought Catholic biblical scholarship into a prominent national position (Dolan 1992, 176).

A third project that O’Hara considered essential to helping Catholics better understand their faith was the translation of the Roman Ritual. Once again the Bishop appointed the best scholars (Gerald. Ellard, SJ, Godfrey Diekmann, OSB and later Theodore Hesburgh, CSC) to undertake “the preparation and presentation of an English version of the °ä´Ç±ô±ô±đł¦łŮľ±´Ç” (Mathis 1956, 301). O’Hara understood that the use of the vernacular in the administration of Catholics rites and sacraments would enhance religious instruction and understanding for all participants. In 1953, the U.S. Bishops approved the translation. “And some months later, during the Archbishop’s (O’Hara’s) visit to Rome for the canonization of Pius X (the Patron of the Confraternity), he was given the good news that the work had been sanctioned by the Sacred Congregation of Rites” (Mathis, 308). Apostolic Delegate, Archbishop Cicognani spoke after O’Hara’s presentation in Rome:

May this translation of the Ritual into English be a true blessing for the

faithful by admitting them to a fuller participation in the sacred ceremonies of the Church. From experience I know how desirous our Catholics have been to understand every phrase of these rites and to profit by the spiritual treasures and inspirations contained in the liturgical prayers. Like another echo of the Gospel, though not a new one, this translation affords a new insight into the message of Christ—fides ex auditu. (Mathis 1956, 309)

With O’Hara’s efforts to revise the Catechism, Bible and Ritual, the English vernacular was introduced to the Church and catechesis was updated to the modern world. Religious education and O’Hara’s dedication to bringing deeper appreciation and understanding of Catholicism to all the people of the Church came to fruition during these years.

Goodwill Movement

No study of O’Hara would be complete without some attention to his role as an apostle of goodwill. O’Hara was named Bishop of Kansas City, Missouri, in 1939. “At the close of his first decade of service. . . . O’Hara was given a singular tribute of honor and affection from his Protestant and Jewish fellow Kansas Citians in recognition of his unique record of collaboration and good fellowship with citizens of all persuasions” (Collins 1975, 1983, 186). He was an advocate for social action and spoke on behalf of minorities and women. He saw that lay women were given leadership roles in local parish and national catechetical organizations. Bishop O’Hara was a strong proponent of minimum wages and racial equality in hospital care. He promoted street preaching and built ten small churches in rural areas with such economy that they gained national attention (Dolan 1992, 221). Additionally, during these years (1945-1953), O’Hara developed an apostolate to Latin America.

The lay apostolate remained an important aspect of Catholic Action and Bishop O’Hara sought to educate Catholic adults by forming discussion groups and setting up Catholic community libraries and reading rooms. He regularly sought the opinions of lay leaders and was ever mindful of their special call to serve the Church. He developed professional training courses and materials for all catechists, clerical, religious and lay alike.

The extent of O’Hara’s humanitarian efforts and the physical growth of his diocese did not go unnoticed in Rome. In June of 1954, O’Hara was named archbishop ad personum.

Acerbo Nimis

1955 marked the golden anniversary of O’Hara’s priesthood. The young priest who had

had given an early sermon on Pope Pius X’s Acerbo Nimis with its warnings about the dangers of religious ignorance, had now given fifty years of his life’s work to alleviate it.

Tirelessly, he planned his schedule for the following year, his last, to be as full as any previous one. On his seventy-fifth birthday, O’Hara flew to New York and then to Paris where he became ill during the celebration of a Mass. After a flight to Milan for an international liturgical conference, the archbishop suffered a heart attack and died at 11:55 on September 11, 1956.

Archbishop Howard of Portland, Oregon, eulogized O’Hara saying,

Devotion to every good cause would seem to summarize the life of Archbishop O’Hara. It is difficult to think of any phase of the Church’s mission in which he was not interested and active. Ranking above all of his interests was, of course, the religious instruction of children. In this country the terms Confraternity and Archbishop O’Hara are almost synonymous. (Collins 1975, 1983, 190)

Bibliography

Archives

Archives of the Diocese of Kansas City—St. Joseph

Archives of the Catholic University of America

The Archives of Marquette University

Archives of the University of Notre Dame

Archives of the Catholic Biblical Association

Archives of the College of St. Thomas

Texts Translated by O’Hara

Dennert, Eberhard. (1904). At the deathbed of Darwinism (Edwin V. O’Hara and John

Pescheges, Trans.). Burlington, IA: University Press.

With the Divine Retreat Master. (1939, 1955). (Edwin O’Hara, Trans.) Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press.

Books

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1911). The pioneer Catholic history of Oregon. Portland OR: Glass and Prudhomme.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1921). A program of Catholic rural action. Washington, DC: NCWC.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1927). The church and the country community. New York: Macmillan.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1929). Catholic evidence work in the United States. Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor Press.

Brochures

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1916). A living wage by legislation: The Oregon experience. Salem, OR: The State of Oregon.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1950). The Parish Confraternity of Christian Doctrine in the United States. Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild.

Published Proceedings

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1921). The rural problem and its bearing on Catholic education. Columbus, OH: National Catholic Education Association, 6.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1935). Activities of the Confraternity. Proceedings of the National Catechetical Congress, 43—55. Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1937). Activities of the Confraternity. Proceedings of the National Catechetical Congress 16—17. Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press.

Articles

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1903a). Religion as a credible doctrine. The Catholic University Bulletin, 9, 78—93.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1903b). The latest defense of Darwinism. Catholic World 80 (480), 719—728.

O’Hara Edwin V. (1903c). Skepticism as a basis of religion. The Catholic University Bulletin, 9, 369—388.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1909). The Catholic girls’ school: Its aims and ideals. The Catholic University Bulletin 15 (5), 456—463.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1910a). Dr. McLoughlin, the father of Oregon. The Catholic University Bulletin, 14 (2), 146—166.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1910b). Francis Norbert Blanchet, The apostle of Oregon. The Catholic University Bulletin 16 (8), 735—760.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1914). The minimum wage. The Catholic University Bulletin 20, (3), 200—210.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1921). A program of Catholic rural action. NCWC Bulletin, 24.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1922a). The church and rural life. St. Isidore’s Plow 1 (1), 1.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1922b). Religious education in rural districts. Catholic School Interests 1, 17.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1922c). Catholic club at state universities. Apologia 1, 14—16.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1923a). The pastor and the working men of his parish. NCWC Bulletin 4 (9) 15—16.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1923b). The school question in Oregon. Catholic World (CXVI), 486.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1923c). The agricultural profession. Catholic World 118, 334—335.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1929a). Sixty hours of religious education. NCWC Bulletin XI (2), 2.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1929b). Religious vacation school. Catholic Education Review 27, 283—295.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1930a). Religious vacation school. The Ecclesiastical Review 82, 463—475.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1930b). Religious vacation school and the diocesan superintendent. Catholic School Journal 30, 200—202.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1930c). Religious vacation schools. Ecclesiastical Review 82, (463—475.

O’Hara, Edwin. V. (1930d). My philosophy of rural life. Commonweal 12 (29), 661—662.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1930e). The rural community and the family. NCWC Review 12, 6.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1931a). The country church and farm family. America 45 (9), 112—114.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1931b). Teaching apologetics in ecclesiastical seminaries and in Catholic colleges for men and women. Journal of Religious Instruction 1, 218—222.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1936a). The Confraternity of Christian Doctrine. Sign 15, 329—330.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1936b). Activities of the Confraternity. Proceedings of the National Catechetical Congress. Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1945). Returned veterans in the parish. American Catholic Sociological Review 6 (1), 23—25.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1956) The Assisi report on Holy Week in the United States in 1956. Worship 39 (9), 548—555.

Addresses

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1905a). “Why I am a Catholic.” Harmony, Minnesota.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1905) “The Catholic church and the American citizen.” Canton, MN.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1920). The rural problem and its bearing on Catholic education. NCEA Proceedings 16.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (4 July, 1922). Freedom of education. Archives of the Diocese of Kansas City

Other Items:

Proceedings of the National Catechetical Congress of the CCD

Catholic Rural Life

St. Isidore’s Plow

Speeches - Proceedings of the National Catechetical Congresses

St Anthony Guild Press, Paterson NJ

Reviews of Edwin V. O’Hara’s Publications:

Ryan, John A. (1928). Dr. O’Hara’s new book offers solution of rural problem. NCWC Bulletin IX (8), 14.

Works about Edwin V. O’Hara

Bryce, Mary Charles, O.S.B. (1976). The Confraternity of Christian Doctrine. In Robert Trisco (Ed.), Catholics in America: 1776—1976 (pp. 149—153). Washington, DC: National Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Bryce, Mary Charles, O.S.B. (1978). Four decades of Roman Catholic innovators. Religious Education 73, Special Issue, 36—57.

Bryce, Mary Charles, O.S.B. (1984). Pride of place: The role of the bishops in the development of catechesis in the United States. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press.

Collins, Joseph B., S.S. (1956). Archbishop Edwin V. O’Hara, D.D., LL. D.: A biographical survey. In The Confraternity comes of age: A historical symposium (pp. 1—26). Paterson, NJ: Confraternity Publications.

Collins, Joseph B., S.S. (1975). Bishop O’Hara and a national CCD. American Ecclesiastical Review 169, 237—255.

Collins, Joseph B., S.S. (1975, 1983). Bishop O’Hara and a national CCD. In Michael Warren (Ed.), Sourcebook for modern catechetics (Vol. 1), (pp. 176—192). Winona, MN: Christian Brothers Publications.

Dolan, Timothy M. (1985). To teach, govern, and sanctify: The life of Edwin Vincent O’Hara (Doctoral dissertation The Catholic University of America, 1985). Dissertation Abstracts International, Religious History 46 (5), 9940.

Dolan, Timothy M. (1992). Some seed fell on good ground: The life of Edwin V. O’Hara. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press.

Marthaler, Berard L. (1987). Grassroots ecumenism and religious education. Ecumenical Trends 16, 65—68.

Marthaler, Berard L. (1990). The rise and decline of the CCD. In Michael Warren (Ed.), Sourcebook for modern catechetics (Vol. 2), (pp. 220—231). Winona, MN: Christian Brothers Publications.

Mathis, Michael A., C.S.C. (1956). Collectio rituum. In The Confraternity comes of age: A historical symposium (pp. 301—310). Paterson, NJ: Confraternity Publications.

Shaw, J. G. (1957). Edwin Vincent O’Hara: American prelate. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Cudahy.

Spellacy, Marie E. (1986). Roman Catholic non-school catechetical ministry before 1930. Religious Education 81 (4), 568—593.

Excerpts from Publications

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1927). The church and the country community. New York: Macmillan.

Why should the Catholic Church urgently concern itself with the farmer? It is simply this. The farm in the United States is the stronghold of childhood. It is there that the religious influence must be set at work if childhood is to be served (23).

The country far excels the city from the standpoint of the most important elements in complete and satisfying human life; namely, in the opportunity for self-employment and for private ownership and above all for wholesome family life (37).

[W]e cannot complacently await the time when all Catholic children will be gathered into our parish schools. Some way must be found, and should be found soon to bring relief to the two million Catholic children who are spiritually starving for systematic religious instruction (60).

[O]ne need have no hesitation in saying that religious vacation schools can be made to go a long way toward supplying this need. The religious vacation school is so far past the mere experimental stage that it can be confidently recommended as of inestimable assistance to the five thousand Catholic pastors who have no parish schools (60-61).

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1936). Diocesan organization of religious study clubs. Proceedings of the National Catechetical Congress. Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press (43-55).

Every thoughtful Catholic must be deeply concerned with the problem of adult education because it is so inextricably interwoven with every effort to advance the cause of religion. Our lay societies will not flourish without enlightened leadership. The lack of such direction has permitted our most ambitious and promising lay organizations to enter on a disastrous decline. Our leading periodicals languish for lack of a Catholic reading public. The ablest writers will exercise their talents in the service of religion in vain is our Catholic people continue to lack interest in topics of intellectual character. . . . The Simple immediate purpose of the religious study club is to improve among its members their mastery of the teaching and practice of the Catholic religion (43-44).

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1937). Activities of the Confraternity. Proceedings of the National Catechetical Congress. Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press (16-17).

It is a great error to suppose that the need of religious education ends when boys and girls have become men and women. All life is a process of education, and religious education no less than political and economic training is necessary for adults.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1956) The Assisi report on Holy Week in the United States in 1956. Worship 39 (9), 548—555.

Renewal of the baptismal vows in the vernacular has had the startling effect of transforming the congregation from spectators to participants. People lose contact with the ceremony in long readings in Latin. All extended responses calling for participation of the people should be in the vernacular.

Recommended Readings

Collins, Joseph B., S.S. (1975, 1983). Bishop O’Hara and a national CCD. In Michael Warren (Ed.), Sourcebook for modern catechetics (Vol. 1), (pp. 176—192). Winona, MN: Christian Brothers Publications.

This short article is written by an expert in catechetical history. Collins makes the claim that O’Hara and the development of CCD in this country are intrinsically linked.

Dolan, Timothy M. (1992). Some seed fell on good ground: The life of Edwin V. O’Hara. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press

This is the definitive and critical full-length biography of O’Hara and is based on the Cardinal’s dissertational work at The Catholic University of America. The text is detailed, includes a chronology of the Bishop’s life and is well-illustrated with photos. This volume contains an excellent essay on the author’s sources.

O’Hara, Edwin V. (1927). The church and the country community. New York: Macmillan.

Perhaps O’Hara’s most significant work, this text helps the reader to understand the centrality of rural life to his ministry and his program for meeting many of its challenges. This book offers a philosophy for the American Catholic rural movement.

Shaw, J. G. (1957). Edwin Vincent O’Hara: American prelate. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Cudahy.

This is an older biography that was published shortly after the Archbishop’s death. Interesting, though uncritical, this text offers insight into O’Hara’s personality and is based on interviews with himshortly before his death.

Author Information

Lucinda A. Nolan

Lucinda A. Nolan is retired Assistant Professor of Religious Education and Catechetics at The Catholic University of America. She earned the Ph.D. in Religion and Religious Education from Fordham University in New York. Dr. Nolan has published numerous articles and is co-editor of Educators in the Catholic Intellectual Tradition (2009). She has taught courses in theology, religious education, faith formation and catechetics at Lewis University, Santa Clara University, St. Elizabeth’s College, Sacred Heart University and Dominican University of California.